It may be necessary for psychic survival but it becomes more false by the day. Thus whatever it was that ‘kept one going’ in the trials of exile, voluntary or not, is a self-preserving fiction.

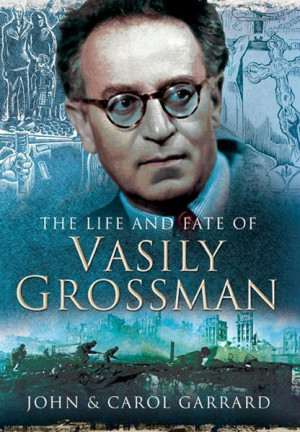

What does remain is a designation empty of any real meaning - countryman, neighbour, friend, relative have no pragmatic import. Stay away long enough, say thirty years or so, and whatever commonality that existed is dissipated by the winds of unshared experience. Living with fixed memories, no matter how accurate, means disappointment in proportion to the time away, for both the traveller and the keepers of the hearth. The real suffering and trauma of exile occurs not in the time away from one’s homeland but upon return. Homer got it wrong in the Odyssey, at least for modern folk. Grossman died of stomach cancer in 1964, not knowing whether his novels would ever be read by the public. His article The Hell of Treblinka (1944) was disseminated at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal as evidence for the prosecution. Grossman's descriptions of ethnic cleansing in Ukraine and Poland, and the liberation of the Treblinka and Majdanek extermination camps, were some of the first eyewitness accounts -as early as 1943-of what later became known as 'The Holocaust'. The novel Stalingrad (1950), later renamed For a Just Cause (За правое дело), is based on his own experiences during the siege. In addition to war journalism, his novels (such as The People are Immortal (Народ бессмертен) were being published in newspapers and he came to be regarded as a legendary war hero. As the war raged on, he covered its major events, including the Battle of Moscow, the Battle of Stalingrad, the Battle of Kursk, and the Battle of Berlin. He became a war reporter for the popular Red Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star). Grossman was exempt from military service, but volunteered for the front, where he spent more than 1,000 days.

When the Great Patriotic War broke out in 1941, Grossman's mother was trapped in Berdichev by the invading German army, and eventually murdered together with 20,000 to 30,000 other Jews who did not evacuate Berdychiv. Young Vasily Grossman idealistically supported the Russian Revolution of 1917. His father had social-democratic convictions and joined the Mensheviks. A Russian nanny turned his name Yossya into Russian Vasya (a diminutive of Vasily), which was accepted by the whole family.

Born Iosif Solomonovich Grossman into an emancipated Jewish family, he did not receive a traditional Jewish education.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)